In the past weeks, we have been experiencing a new way of living, working, and thinking. When the State of Emergency was announced as the Covid-19 crisis hit South Africa, a new set of rules began to form, and with it a new set of questions and challenges.

South Africans may have understood what needed to be done, but we also understood one rule would be almost impossible for the majority of our Country – “social distancing”, or as we prefer, Physical Distancing – and the disparity between those who can, and those who cannot.

As Urban Designers, this raises questions within our field for the design of our cities and future developments. We were once heading towards the era of Smart Cities; a technological buzz phrase that refers to cities that bring together infrastructure and technology to improve the quality of life of citizens and enhance their interactions with the urban environment.

Also Read: Appropriate steps to implementing social distancing in a construction site

Given this time we are living in, we feel it is worth revisiting this path. The global pandemic has highlighted how precious our space is, for our health and well being and for our communities to survive. Is the Smart City really our best future, and can it provide genuine solutions we need to our very real problems?

Understanding our goal

The goal of a Smart City is transformational: to achieve an enhanced quality of life for citizens. Even before COVID-19, “Smart Cities” was a buzz phrase that appeared frequently in government members’ speeches and budgets. South African cities are not as evolved as say New York or London and offer the opportunity to build the technology of Smart Cities into their framework much more easily.

Until now, what we have seen of the South African “Smart City” showcase towers of glass and steel, mass surveillance, non-contextualised urban places, and a lack of focus on the real urban issues of poverty, social-economic and spatial inequality in our society.

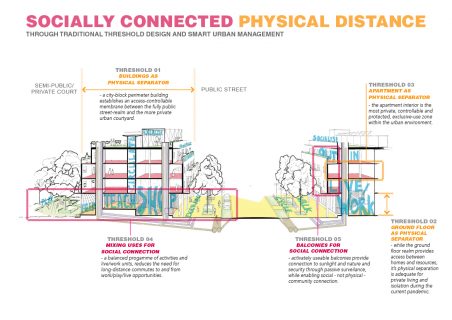

With this technocratic focus, the Smart City has diverted attention away from common sense architecture and Traditional Urbanism – ideas that can deal with our global climate and urban crisis.

In our opinion, the real Smart City can be found through Traditional Urbanism, with its livable and sustainable places designed for the people. This thinking incorporates some technologies to monitor infrastructure efficiency and can be coupled with some “smart city” technology but should at its core promote civil liberties.

How COVID-19 and social distancing can change design thinking

Smart Cities in the time of physical distancing means that firstly we need to remove that term. “Social distancing” leads to discrimination as is apparent in the reports of Africans living in China and Chinese living in Africa. The focus should be on “Physical Distancing” in the urban context. Physical distance does not discriminate based on race, economic standing, or culture.

We believe the rationale for Traditional Urban design, incorporating “smart technologies”, will become stronger considering the Covid-19 pandemic in South Africa.

There is an even greater need for urban places where all people can live and flourish, with room to breathe.

Even when we return to a sense of somewhat ‘normal’, urban cities will continue to be viewed as ideal places for living and working, as well as shopping and playing. But greater responsibility will fall on local community urban designers to plan and build spaces that will accommodate the new functions from lessons we are learning during this pandemic. The provision and need for quality outdoor places will increase, to improve the health of all citizens. These areas and their amenities are essential to allow new, small businesses to grow and flourish.

How do we get there?

In our opinion, the ideal South African “smart city” does not yet exist. In order to aid city building with physical distancing in mind we should plan to build cities in the traditional way again.

For South African, that means we must fast-track the total eradication of urban slums. COVID-19 has shown how socially, spatially, and economically unequal we are. This must be the focus for government, urban practitioners, civil society, and communities. It is not just about the COVID-19, but rather to eradicate poor underserved areas that can potentially become the incubator for health pandemics.

All good International examples of traditional, smart city design are cities without slums. In Germany, Bahnstadt and Heidelberg offer a balanced approach between Traditional Urbanism, applied “smart city” technologies and public spaces for their communities. In Florida, America, the Seaside towns take a similar, balanced vernacular approach by combining Traditional Urbanism with applied technologies to fit the context, thereby building healthy communities and equality within society.

More Traditional Urbanism examples exist within Africa itself, including the cities of Casablanca, São Filipe and Timbuktu – examples where heritage and modern city design meet and merge to create anchors for the communutes.

For South Africa to achieve this, we believe the focus should shift back on Traditional Cities with some “smart city” technologies. This will contribute towards the restoration of existing urban centres and towns within coherent metropolitan regions; the reconfiguration of sprawling suburbs into communities of real neighbourhoods and diverse districts; the conservation of natural environments; and the preservation of our built legacy.

South African architecture and design already has a framework vision for urban planning into 2040. The 2014 Spatial Framework places the onus on developers to adapt to these guidelines, which includes provision for affordable housing. We have already seen projects that ignore these guidelines and fail. Our job as Urban and Architectural designers is to take this vision and move it forward even further. This can be done through combining Traditional Urbanism with Smart City technology.

How quickly could we achieve this?

Covid-19 presents us with a window of opportunity – to re-establish cooperation between our citizens, and local, provincial and national government to make our plans human-centric. The key will lie in planning and working with our government to achieve this. The steps will be incremental, but if we move towards a Traditional City design, we can build strong, healthy communities.

Our legacy as urban designers and architects is tested over many decades and generations. We cannot assume this type of crisis will be the last, but we can choose to use these lessons and design for the future. Cities take a long time to build, but if you design them correctly, they could stand the test of time and withstand any potential future pandemic.

We need to look back, to traditional urban design practices, to find our way forward.

Leave a Reply