X-Tu Architects takes us through the design considerations and intentions of Jeongok Prehistory Museum in South Korea

X-Tu Architects takes us through the design considerations and intentions of Jeongok Prehistory Museum in South Korea

Located on a paleolithic site of major archeological significance in Jeongok, South Korea, the facility aims to provide a multi-sensory space that represents ranging environments and atmospheres from the prehistoric landscape.

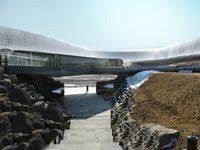

Stretching between two small peaks, the structure seeks to harmoniously co-exist with the natural surroundings, physically acting as a threshold between modern day and archaic times. The soft and rounded form meanders around the site, paying homage to the watery landscape that originally existed nearby.

A perforated double wall referencing the pattern of reptile skin reflects the peripheral scenery, changing as the day progresses and activity around the volume evolves. At night, the small punctures become illuminated and animated, as light moves along the stainless steel which smoothly wraps around the tubular form.

Paths organized as overlapping loops circulate around the building and serve as exterior museographic spaces. Merging the boundaries of indoors and out, concealed and exposed, the design aims to put users closer to the landscape than the building.

Inside; a network of exhibition, education and activity spaces work in a continuous loop, guiding visitors through a collection of open and interactive areas. Freely arranged islands form micro-themed atmospheres throughout the museum, whose environment replicates and reconstitutes scenic landscapes and animal species.

The museum focuses on themes in the natural history of the Chugaryeong rift valley, and features fossil skeleton models of human evolution, human and animal adaptations to the environment, and restorations of cave paintings. Outside, the landscape has been restored to the original state as a natural riverside park.

We wished the visitors to live an experience, to meet primitive mankind and to be introduced into a world different from everyday life, nearer the landscape than the building. Paleolithic men were not living like us in standardized built places. They kept moving in the landscape, the forests, the stream valleys, the delta marshes of which they knew every meander. The rocks and the bare ground were their everyday life, as familiar to them as the house floor to us.

Outside, it is a threshold, a bridge that spans the precipice. Inside, the project seems entirely made out of the same material, an archaic and primitive material, as if it had been shaped out of the cliff itself. A double metal envelope with various perforations, waving and soft, nearly organic, the front shimmers like a reptile skin ; more or less glazed according to different places, changing with the light, it becomes a stainless steel mirror underneath which reflects the image of the chasm.

The museum, a threshold to the Prehistory Park

From the motorway, the museum looks like a strange and immaterial volume, softly glimmering, stretched between two cliffs. Around it the landscape has been restored, cleared of its undesirable buildings, and given back its original identity as a natural riverside site. The parking places disappear under the trees on the eastern side of the place. With its new trees the site recovers its primitive ecosystem. A walk along the rift gets the visitor into condition. Like the primitive men, he progresses along the meander, amid wild graminaceae.

The rift deepens along with the feeling of suspense as he is coming nearer…The museum appears, enchased in the cliff. Then on its stain-steel mirror underface, the reflection of the chasm is suddenly unveiled, and at last the chasm itself is revealed and the visitor will have to cross over on a foot-bridge. Having crossed the chasm, he reaches the only entrance to the museum and the Prehistory Park. In the museum, a circular way which extends into the Prehistory Park.

On top of the stairs, an open space gives access to the reception, the entrance to the museum and the exhibition, the cafeteria, the lecture-room, the pedagogic activities and the multimedia laboratory. The visitor walks all around the factual parts of the project: temporary exhibitions and lecture-room. Back at the open space he can go again to the shop or the museum. The pedagogic and multimedia activities can be seen from outside, as the rooms are open, so that the visitor is encouraged to take part.

Rooms and halls are conceived like landscapes

Primitive men were not living in « rooms » but in open spaces. Living near the river they roamed freely along the country meanders. Their roaming made the paths which gave the site a structure. The inside of the museum and its scenographic course have been conceived after that image, like a landscape. The paths from theme to theme made by the flow of visitors meet part freely and allow going back.

An envelope for services clears the space

The walls of various thickness contain all the services needed for the building and the museum structure, fluids, ventilation, electricity, audio and lighting equipment, as well as show windows for the museum, pedagogic stocks, bar, lavatories, technical rooms. The walls are uninterrupted from floor to ceiling, so that the network can evolve, when necessary all around the building.

The envelope filters the light like a lattice. The double wall includes glazings and solar protections in perforated metal and makes it possible to have a perfect command of heat exchange of the building, in winter as in summer. The admission of natural light is adjustable according to the needs of scenographic effects. On the level of the cafeteria and the central space, panoramic windows open on the landscape.

The scenography

Our purpose: A scenography able to evolve with the progress of research.

Allow the visitor to share the emotion of the paleontologist who discovers the prints of a child’s naked feet on the soft soil of a cave.

The project offers evolutive scenographic tools to be combined;

The image walls for texts, plans, drawings and movie showing.

The service walls which will contain new show windows as research progresses

Malleable recomposable white mud floor; to reconstruct archeological sites and feel the emotion of the site inventor

The service columns; to make up the landscape and evolve from area to area or from era to era According to their position, they bring light, support projection or fitting equipment.

Entrances are freely organized in archipelagos which constitute thematic micro-spaces.

Electricity and audio work-nets are regularly distributed in the ceilings.

The sequences:

The presentation about the paleolithic era in Jeongok site

The human evolution during the prehistoric era; the various ages progress in the archipelago of the service columns. The large arrangement reconstructing an archeological excavation site : it can be seen from the entrance and it is meant to attract visitors but it is not wholly discovered until the end of the visit.

The common scenographic spaces

The interactive multimedia space is free of access and common to the temporary exhibition and the museum.

The “Chasm doms”, transparent port-holes directed toward the void make it possible to see the pit.

The balcony over the pit where we come within an ace of the abyss before leaving towards the out side museographic space and the view-point on top of the hill (prehistory park)

A walk in the prehistory park is shaped as a circular path which leads back to the central reception space.

The pedagogic workrooms and the multimedia lab

The workroom is equipped like the museographic hall with malleable mud floor for the teaching of archeological methods, with walls meant for projections and walls meant for paleolithic rock painting, and on the floor are scattered boulders on which to sit when working flint. The multimedia lab is arranged as an extension of the cafeteria as it can be used either as a group activity or an archeological Internet café.

The inside functions of the museum and the deliveries

The administration and research office and the staff restroom are located along the exhibition spaces, near at hand for the setting of new exhibitions. Stock-rooms for non exhibited collections and the maintenance rooms are located under the showroom, and served by a goods-lift from the upstairs level of “the prehistory park”.

So, the organization of the building takes advantage of the double access made possible by the location on a slope: visitors in the lower part and deliveries on top of the cliff, out of the opening hours.

Architectural Intentions

On the river side, in a winding landscape, a bridge stretched between two cliffs, a threshold, a bridge spanning a precipice

We wished to honour the riverside landscape which saw the birth of the first inhabitants of Korea, and acknowledge the beauty of the two hill curves echoing the river meanders.

How to enhance such a pre-existent form and its geological underground chasm?By;-

Digging the chasm to let the Earth tell its history

Alleviating the visual hold of the project in order to let the chasm express itself ;

For this purpose, the building will be enchased into the hill which has been hollowed out and the stockrooms will be located underground

By curving the central part of the building so as to unveil the geological crack (and also the sun, from the edge of the crack)

By clothing it in a shimmering skin which will reflect the precipice from underneath

Thus set up, the project appears like a bridge stretched between two cliffs which can be seen from a long distance from the motorway.

The precipice as a natural threshold and the emotion it induces, will be used to realize a symbolic threshold into the prehistoric era which will also give access to the prehistory park.

Then we create paths, many paths around the curves of the project and of the cliffs, because the paths which were made by the animals going down to the river to drink belonged to the first human beings landscape.

An immaterial-abstract-shaped time vessel

We want to travel through history!

We wished the visitors to live an experience, to meet primitive mankind and to be introduced into a world different from everyday life, nearer the landscape than the building.

Paleolithic men were not living like us in standardized built places. They kept moving in the landscape, the forests, the stream valleys, the delta marshes of which they knew every meander. The rocks and the bare ground were their everyday life, as familiar to them as the house floor to us.

Such a physical and intellectual experience has its own course but it also breaks with the usual form referents and resorts to abstract and immaterial forms to :

Let the site geography speak

Let the museographic arrangements inside speak

Outside, it is a threshold, a bridge that spans the precipice.

Inside, the project seems entirely made out of the same material, an archaic and primitive material, as if it had been shaped out of the cliff itself.

One with the abyss and with a shimmering envelope

A double metal envelope with various perforations, waving and soft, nearly organic, the front shimmers like a reptile skin ; more or less glazed according to different places, changing with the light, it becomes a stainless steel mirror underneath which reflects the image of the chasm.

Project Questionnaire:

It took about a year to conclude the contract, and above all, the shape of the building changed. That’s why the completion was put off. A survey around the lot discovered the remains of a Goguryeo fortress. So we had no choice but to change the original plan.

As I mentioned, we had to preserve the remains of the fortress. So we had no alternative but to modify the design. As we had to adjust the mass in a way that does not intrude on the remains of the fortress, the original single mass was divided into two. Also, the height of the building was increased compared to previously. The middle of the building has the structure of a 30m-long bridge. To support it structurally, the structure itself became thicker. According to the original plan, the length of the bridge was 50m, and thus the building itself was much longer and thinner. If a bridge structure is 50m during the construction document stage, it will cost a lot to resolve it structurally. Accordingly, in order to cut down on construction costs, we changed the location so that we can reduce the gap between the hills on which the building sits, and that’s why we chose the current 30m bridge structure.

There is a topographical reason too. We planned the design competition on the assumption that the topography was deeply concave like a valley. When we surveyed the topography after we won the competition, however, the hills were lower than we thought, and the valley was not that deep. So the design we submitted during the design competition looks somewhat different than the building you see now. The area around the lot used to be a densely wooded forest. We cut down all the trees during the construction. If the building, trees and hills harmonized with one another as we planned, the structure would have looked natural as if it had descended on the ground.

That part was supposed to be a large mass connected to the exhibition space, but as the mass was divided due to the ruins, the curve was greatly reduced. So the apparent finish felt harder than the soft feeling of a curve. As the curved surface was large according to the initial plan, the curve was soft and had no visual problem, but since the mass was divided, it felt compressed a great deal. Because the mass surrounding the restaurant was small, if panels are cut and pasted, the angles seemed to go against the overall atmosphere, visually. As it seemed to spoil the harmony topographically, we cut out the surface to remove it. I don’t remember when there were a lot of trees, but now that the trees are all gone, the restaurant seems to stand out quite a bit. We took those elements into consideration and tidied up the mass.

Another reason was that, as the remaining space was related to the exhibition function of the museum, it is a covered space cut off from the outside, but the restaurant is a space where people are in motion. In other words, we planned to open up the space so that people could come and go, and use it as a terrace.

In Jeongok around 400 stone axes were discovered. The archeological value of these remains is huge not only in Korea, but also across Asia. In Asia including Korea, however, there was no museum displaying prehistoric relics. Therefore, we wanted to highlight the historical meaning and value of Jeongok and connect it to the history of mankind in Asia, thereby giving it a greater meaning. So we allocated an exhibition space to the civilization of mankind.

Not only to display stone axes, but also to reproduce the life of prehistoric mankind, we included the ecosystem of Jeongok in the exhibition space. We conducted a research jointly with museum director Bae Gi-dong and several curators, and found that world-famous anthropology museums as of late are changing. They used to have displays about man only, but now they try to piece together the relationship between man and nature. We wanted to integrate the relationship between the history of mankind and the eco- system to put out a display in a new way.

It was quite difficult at first to build a museum exclusively for hand axes. So we studied how to configure the exhibition program together with museum officials and French experts. The museum officials and us visited many museums in Europe and Asia, and decided to reinforce the contents about the history of mankind and ecosystems. Each museum we visited had very different display formats. If France focused on the visual aspects, the UK focused on experience. We wanted to create a space in the Jeongok Prehistory Museum where visitors could directly experience something.

We paid great attention to details as well. For instance, if the existing model of mankind was Western-centric, we wanted to reproduce the face and physique of an Asian on the basis of professional advice.

The building has a double skin: the stainless steel and an empty space in the middle. Air can be circulated through this empty space. The air escapes through the small holes of the building, and heat also escapes. Also, while covering the building, the outer skin creates a shade on the inside the building, thereby resolving the problem of heat circulation.

Someone pointed out the reflexivity of the stainless steel. At first, we considered using translucent stainless steel with a lower reflexivity. But the color of the soil is red clay, and if a building finished with translucent stainless steel was constructed on it, we thought the atmosphere might be somewhat somber. And as the area has a lot of dirt.

If dust or dirt smears the building, it may look drabber. So we thought it might be better off to use something shiny. It can give a brisk and sparky feeling. But the important thing was to use shiny materials in line with the museum concept of “a spaceship going back in time” to ensure that the surrounding scenery would be reflected. It was important to make sure the building reflects the ever changing images throughout the four seasons.

What was the most difficult structurally?

It is obvious that the tough subject was to realize the curved beams. Indeed, those beams had to follow the organic design of the Museum. Meanwhile, we also had to reduce and control the global height of the building, regarding to the path on the roof, and the goal of creating a bridge between both hills.

The Jeongok Museum exhibit project has been developed around Prehistoric Jeongok man and his great family of the hominids. In order to underline the uniqueness and complexity of the Korean prehistoric society, it was important to situate Jeongok Man and his productions into the largest paleoanthropological and cultural context as possible. Therefore it has been decided to approach him through 4 different themes.

The first theme deals with the hominids and the human families throughout the world and time with a focus on Far East Asia, Korea and Jeongok. Casts of original fossils of hominids from Pre-Australopithecus to Homo sapiens through Homo erectus will be present along with description notes. Each fossil will have its reconstitution for a total of 15 reconstitutions, which will take place in the centre of the exhibition room and form the Great march of evolution.

The second theme will concern the environment including flora and fauna corresponding to each hominid group. Thus, the arborated savana, the tropical jungle, the cold and temperate continental environment will be reconstituted.

The third theme will focus on the origin of bipedalism and the ability of exploring new areas with a focus on human migrations and the different routes chosen by humans through time and regions displayed on a giant terrestrial globe.

The fourth theme will take into consideration the human technological and cultural productions, including stonet tool making process, which tools panoply will induce ability to develop means of subsistence such as hunting and gatherings. There the Jeongok site ecological and archaeological particularities will be presented. The Jeongok stone-tools industry will be presented in a gigantic column in order to show the complexity and variety of this lithic industry. Production and use of fire will also be evoked.

Architects + Museography: X-TU Architects + Nicola DESMAZIERE + Anouk LEGENDRE

Team: Gaelle Leborgne, Olivier Busson, Mathias Lukacs, Keeyong Lee, Amelie Busin, Alix Pellen, Seung-Eun Lee, Mélanie Bury, Nenad Basic

Client: Gyeonggi government

Program: Cultural Museum of prehistory

Name of Project: JEONGOK PREHISTORY MUSEUM

Location: Jeongok, South korea

Project type: Building

Project Duration: June 2008- May 2011

Total floor area: 6 700 m² shon

Total site area: 72.600 m²

Cost: 48 m equivalent € [building + museography + landscape]

Engineering consortium: SAC int. _ Architects/ing _ Séoul

Sous-traitants: RFR _ Engineering structur, façads Alto ingenierie _ Engineering fluids

8’18’’ _ Lighting

OGI _ Bet vrd

Lord Cultur _ Muséographic consultant

F. Demeter _ Scientific consultant

Jeongok prehistory museum by X-Tu architects, jeongok, South Korea. Images courtesy of X-Tu architects

Approaching the museum

Pathways leading to ‘threshold’

Threshold

Beneath the structure

The reflective facade changes with light conditions and activity.

Windows

Prehistoric garden

Overall view

Interior

Corridor while under construction

Restaurant while under Construction

Exhibition space while under Construction

Stairway while under construction

X_TU FIRM PROFILE

Anouk Legendre + Nicolas Desmazieres

Through several buildings, they have built up a refined language, precise, which is expressed by serene and light volumes, placed frankly and therefore withhold a unique force of impact. A spirit of “minimalism” has been evoked in their consideration, but it would be, without doubt, more true to see it as, shapes poetically implied in their volumes with the fullness of their materials. The energy put in their constructions, the rational use of the construction resources, robust details, frank color scheme giving a balance between blocks and large spaces show that all entities are treated very distinctly.

The aptness and the refusal of ostentation represent a very demanding patience and research. The main lines of their buildings contain sobriety providing from strong images thoroughly settled, images which appear from the observations of powerful sites.